|

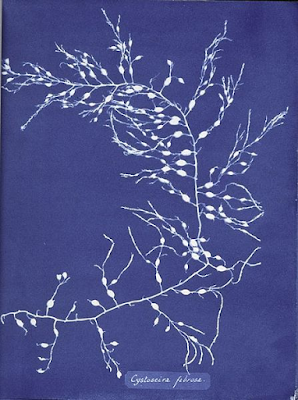

| One of the plates in Atkins' "Photographs of British Algae - Cyanotype Impressions." |

You won't know this, but I have a qualification in Printmaking from this very establishment. And so, it's of interest to me that there exists an interesting Seaweed/Printmaking crossover. It's very relevant to the history of Identifying Things and might even inspire you in the display of your own specimens.

Anna Atkins was born in Kent in 1799. Her father was a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, so she had science in her blood (and the advantage of being born into a family where money wasn't a problem). He translated French scientist Jean-Baptiste de Monet Lamarck's "Genera of Shells" into English. And she provided the illustrations of the shells (ah yes I knew I'd squeeze snails into this somehow). You can see them here on Flickr.

But that's by the by really. The point is, through her father she met William Henry Fox Talbot (who lived not far from here) who was the chap who created the first photographic negative image. She took up photography and so would have been one of the first women to do so. Her father also knew John Herschel (son of astronomer William Herschel) who was instrumental in improving photographic processes. He invented the cyanotype. Under his mentoring, Anna Atkins mastered this technique.

|

| Anna Atkins in 1861, singlehandedly supporting the British fabric industry |

Atkins used this technique to produce the world's first ever book produced entirely by photographic means, which was published in four volumes between 1843 and 53. She'd have to have made them all individually of course! So only 13 copies are known. But thanks to the marvels of the internet, you can see selected plates here at Flickr, or if you're interested, the New York Public Library has all four volumes for you to look at.

I tell you what, if anyone wants to have a go, I've got the chemicals... you're more than welcome.

Highlighting her motivation, she says in her introduction: "The difficulty of making accurate drawings of obects as minute as many of the Algae and Confervae, has induced me to avail myself of Sir John Herschel's beautiful process of Cyanotype [...]". Cyanotype's not very good for handwriting though, I can't read the rest very well! But whatever, as a result of the book, photography was established as an acceptable, accurate way of producing scientific illustrations.

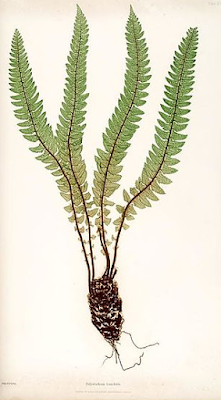

After this Anna turned her attention to another Victorian favourite, making cyanotypes of ferns.

|

| Atkins' cyanotype of bracken |

So there we have it, a female science/art pioneer. However, it wasn't all carefree larking about with plants and chemicals for women in those days. I read in this article which notes that although she was elected as a member of the Botanical Society of London, women members weren't allowed to speak at meetings and nor could they hold office. At least Science has moved on since then (though I hear some golf clubs are still struggling with the concept).

|

| From Bradbury's fern book |

|

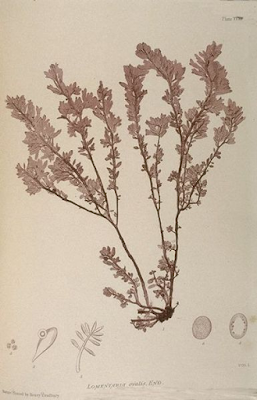

| One of Bradbury's nature-printed seaweeds. |

No comments :

Post a Comment