|

| White Nothe headland (CC Jim Champion) |

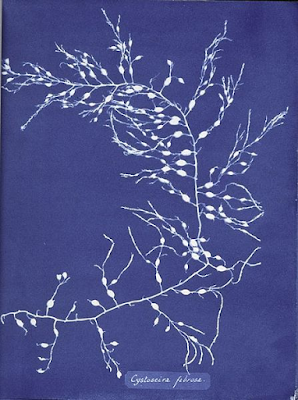

It's very interesting embarking on a new group of flora or fauna though. It's interesting how you don't even realise how little you know. I thought 'oh yeah, I know a few seaweeds' - but I don't really. I know as much about seaweeds as a botanist who can distinguish a dandelion from a nettle. But you have to start somewhere. And that's one of the first useful things you can feel your brain doing - noticing that one specimen is different from another, even if you don't know their names.

I soon realised there were a lot of different seaweeds washed up on the beach. And some of them were in a place I'd not thought about before: they were tiny and growing on other seaweeds. I suppose it's like when I first got interested in snails, in that not all UK snails are shaped like the familiar garden snail - some are tall and pointy, some are super tiny, some are even spikey. I like the sensation of a hidden world becoming revealed. Yes, you will become one of the Initiated. (It's surely no worse a use of your brain than knowing all the minutiae of the football league or what the latest technological must-have is, and you could even use your knowledge to help protect the natural world).

|

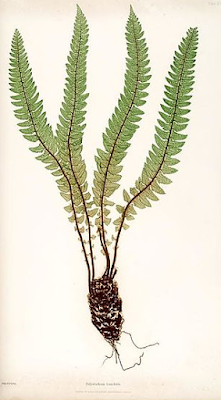

| Calliblepharis cilliata - how could you not like all those weird eyelashy outgrowths? |

That's one reason why you shouldn't leave all your collecting until the last minute, because it takes time to realise what the best techniques are for dealing with your specimens.

But another reason is that you need some time collecting and observing to start recognising what you've seen already, and to be able to pick out what's new. At first you don't see everything - you can only take in the broad picture, and you'll overlook all sorts of weird and wonderful things. It's that extra stage that can only happen with time really. This is an assigment you can get a good mark on - you just need to give yourself a bit of time to do yourself and it justice. That's my advice.

I bought a new seaweed book. Of course. I should stop spending all my wages on books, but there always seems to be another interesting one to be had. I must realise that owning a book does not equate to knowing or understanding the information in it, though.

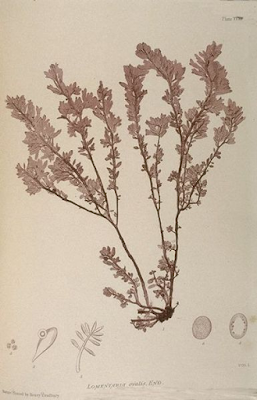

My new purchase is 'Seaweeds of Britain and Ireland' (2nd ed.) by Bunker, Brodie, Maggs and Bunker (2017). Keen seaweed student F also has a copy and has apparently been finding it very useful. The photos certainly seem very clear and there's a lot of description and information. I felt a bit overwhelmed thinking about the number of species (the book has over 200 and there are over 600 around the UK - who knew). But they're such beautiful things and I do want to try to recognise a few more than my current paltry efforts. I recommend. You're welcome to come and look at my copy also.

I have been looking at the Seasearch website (the instigators of the book), and if you're keen on diving they run identification courses around the British Isles - the idea being that you can then go out and start recording sea creatures and seaweeds for yourself, or on one of their special survey days. Imagine the fun (if only I could trust myself not to drown).