|

| Mycologists out on a fungal foray (baskets not obligatory). CC MJ Richardson. |

Thomas Bruges Flower in 'The Flora of Wiltshire' (Wiltshire Arch. and Nat. Hist. Magazine, v4. 1858) *He probably meant it in a non-gender-specific way really, but it was 1858 so maybe we ought to let him off. (Did you notice has one of those mad Nominative Determinism surnames?)

His point (and mine), is that getting outside and seeing what species are out there (especially in the company of like minded people), can have excellent long-term effects on your state of mind.

I know this collection is one of your assignments (and so you may feel it is only adding to the pressures you are under), but in my own experience I think it has elements which are quite stress-reducing.

I'm a bit of a serial course-taker, and a while ago I was studying part-time over at one of the other campuses. Everything started off very positively, but half-way through I got really confused and anxious about what I was doing (to the point where I'd sometimes avoid coming in, and that, as I'm sure you know, is not a good idea, as speaking to people always helps sort things out. It worked out ok in the end btw). So I think this assignment is good because once you've settled on a group to collect, what you have to do is very well set out. That clarity makes things a bit easier, and causes less stress.

|

| Being outdoors is good for you. CC image John Chroston. |

A positive element of this assignment is the element of choice. You come to this course with existing interests and prior experiences, and might want to draw on those to inspire which group to choose. You might want to pursue something requiring skills you already have (maybe you enjoy fiddly practical tasks), or that will encourage you to get out to habitats you're interested in. Or, you might want to try something entirely new: don't be deterred by prior ideas of what you're good at, as the human brain is amazingly flexible (at any age!). Have confidence.

|

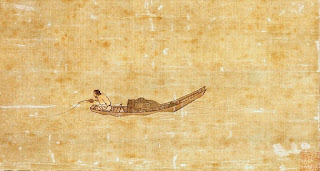

| I can imagine the mental benefits of going out in a boat (not so confident of a fish's perspective of angling though). This Chinese depiction by Ma Yuan is from 1195AD! |

Another aspect of 'snailing' or 'ferning' or whatever it is you choose, is it can really take you out of yourself. I mean that focused state of mind when you're entirely engrossed in what you're doing. Maybe it'll happen when you're out searching for specimens, but I definitely experience it when I'm hunched over the microscope in the lab, staring at the keys and scribbling into my notebook. (I recognise it elsewhere from when I'm being arty, drawing and painting - maybe you have your own version too). It happens when you're absorbed in making sketches and descriptions from your own close observations, and checking and comparing the details of your specimen back and forth with the drawings and descriptions in the ID books. You're not thinking about anything else, and it's like a puzzle to be solved. Sometimes you can get cross when you can't work out the final answer, though even then you'll have been usefully observing and recording new and interesting things (in the case of the microscopic worlds of lichens, beetles and so on, probably features you'd never have suspected). But when your efforts result in triumph, and you get a successful identification, then you will feel rightly chuffed, and I think that's a very satisfying sensation.

|

| This isn't your brain on drugs - this is your brain whilst doing your taxonomic collection. Probably. |